Legal Status of the Caspian Sea in the context of oil and gas disputes

This article is based on the talk which the author gave at the 12th American Bar Association-Russian Arbitration Association Annual Conference on Resolution of CIS-related Disputes, in a session on “CIS-related Oil and Gas Disputes” on 16th September 2020. It focuses on the legal status of the Caspian Sea relating to oil and gas exploration and production (and does not cover other aspects of such as fishing and navigation).

Although Winston Churchill’s dictum of October 1939 – “Russia…is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma” – long ago ceased to apply generally, the legal status of the Caspian Sea has remained perplexing. Many issues have been resolved by the signature of the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea in 2018, but there are some still outstanding.

Background – sea or lake?

What were the main issues?

Before 1991, there were only two littoral states with coastlines on the Caspian – the USSR and Iran. There were treaties between Russia and Iran as far back as 1729, and those current at the breakup of the Soviet Union were the Treaty on Friendship and Cooperation of 1921 and the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation of 1940.

The treaties did not deal with petroleum exploitation rights for the simple reason that, in those days, relevant activity took place onshore, and there was relatively little interest – either locally or internationally - in production from offshore areas. As indicated below, that began to change internationally immediately after World War II, and in time this also extended to the Caspian.

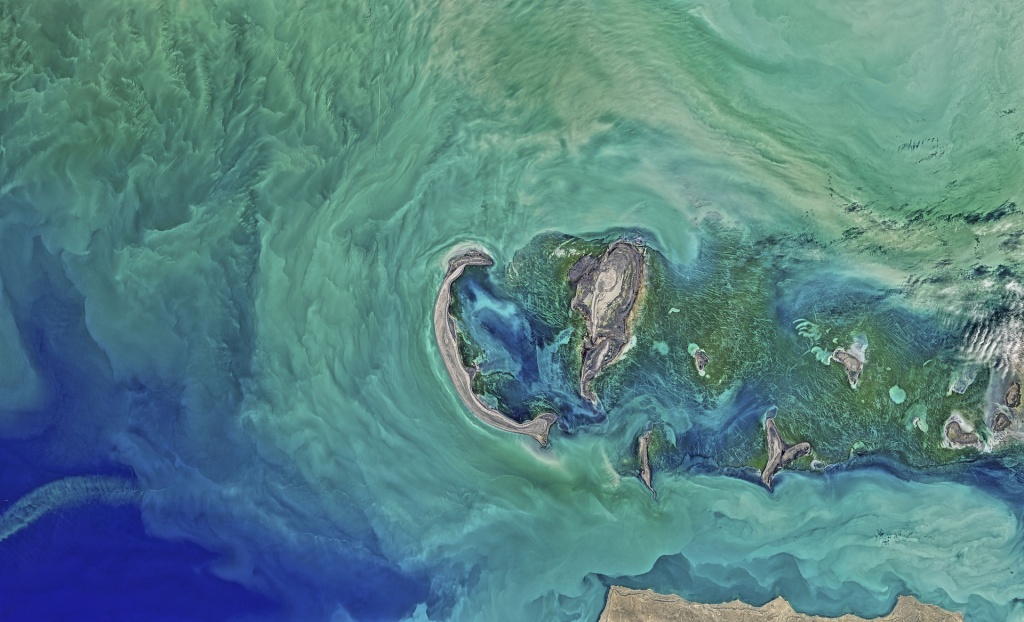

After the break-up of the Soviet Union, the situation in relation to the Caspian was complicated by disagreement amongst the five littoral states, four of them newly-independent, as to whether it should be treated legally as a sea or a lake– or something sui generis which is neither a sea nor a lake. The distinction was important because, if it were a sea, there was by the early 1990s a well-developed body of law and jurisprudence which would apply. If not, then the situation was unclear.

The Caspian is called a sea. It is salty and big, and it can be stormy. However, it is wholly enclosed by land and does not connect with any other body of water. It is difficult to pin down a legally binding definition, but there is a considerable body of opinion, although not universally held, that, for a body of water to be characterised as a sea legally, it must connect with another sea or an ocean and not, as in the case of the Caspian, through rivers and other (non-salty) bodies of water.

What does public international law say about seas?

The application of public international law to the continental shelf began in September 1945, immediately after World War II ended in both Europe and the Far East. President Harry Truman proclaimed that “the United States regards the natural resources of the subsoil and sea bed of the continental shelf beneath the high seas but contiguous to the coasts of the United States as appertaining to the United States, subject to its jurisdiction and control.” The US was primarily interested in exploiting the resources of the Gulf of Mexico, but numerous other states followed this initiative with similar declarations in respect of areas adjacent to their coasts.

The Truman proclamation also declared that “in cases where the continental shelf extends to the shores of another State, or is shared with an adjacent State, the boundary shall be determined by the United States and the State concerned in accordance with equitable principles”. The high seas above the continental shelf and rights to navigation were to be in no way affected.

In the ensuing years, a substantial jurisprudence developed around these concepts in a series of decisions of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) relating to boundary disputes between countries mainly in Europe and North Africa. Also, the United Nations organised a commission and conference which culminated in the Geneva Convention of 1958 (consisting of four treaties). It attracted widespread adherence amongst coastal states, although a number registered reservations to qualify their acceptance. Subsequent decisions of the ICJ recognised that that there was a body of customary international law which was, in effect, reflected in the 1958 Convention.

The ICJ’s decisions – both before and after 1958 – resulted in the establishment of the “equidistance/special circumstances principle”, which takes into account the general configuration of coastlines but also special features such as islands and projections and, in addition, proportionality between length of coastline and extent of continental shelf.

The United Nations organised a further conference which resulted in the even more wide-ranging Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982 (UNCLOS). UNCLOS reaffirmed the principles in the 1958 Convention and the decisions of the ICJ as reflecting customary international law. However, although UNCLOS had an even larger number of adherents, some significant states – most notably the United States but also, most relevant in the context of the Caspian, Iran, and Turkmenistan – did not adopt it.

So, what, if it’s not a sea?

It is beyond the scope of a relatively brief article of this kind to go through all the detailed, conflicting arguments that were brought into the discussions about the Caspian over a period of nearly 20 years. These can, nonetheless, be very briefly summarised in a few bullet points which are simplified for the purposes of this article and, of course, mutually contradictory.

-

The rights of the littoral states can only be resolved jointly, i.e. nothing applies unless they all agree.

-

Iran is entitled to 50 per cent, and the others are together entitled to 50 per cent.

- As there are five states, each is entitled to 20 per cent.

- The rights should be determined under public international law anyway, i.e. under the “equidistance/special circumstances” principle. Tempting as it may have been for the others to follow the latter, because of the way the projections at the borderlines in the southern Caspian work out, Iran would have been entitled to less than 15 per cent on that basis. For a country which was co-equal with the Soviet Union under the previous regime (or thought it was), this was not readily acceptable.

So how were the areas that have been exploited – i.e. in the northern part of the Caspian – dealt with? Treaties between states (bilateral and trilateral)

It should be remembered that large-scale petroleum production in the Russian empire began in Azerbaijan during the 19th century and accelerated after the arrival of the Nobel brothers in Baku in the 1870s. The oilfields in Azerbaijan (all onshore at that time) continued to be prolific oil producers during the Soviet period. After World War II, with the onshore oil resources becoming depleted, attention turned to the offshore areas. However, it was not until after the break-up of the Soviet Union that the international petroleum industry really arrived in Azerbaijan, resulting in the “Contract of the Century” being signed in 1994. Following the discovery of the Shah Deniz field in 1999, Azerbaijan also became a significant offshore gas producer.

A 1970 decree of the USSR Ministry of Oil and Gas Industry had established administrative zones for subsoil activity in the Caspian among the four littoral republics. However, this decree served domestic purposes. In the initial period after the break-up of the Soviet Union, there were no treaties between the new sovereign states governing the exploitation of the petroleum resources of the Caspian seabed and subsoil. The fields exploited by Azerbaijan were, however, clearly within areas that would have been subject to its jurisdiction had the “equidistance/special circumstances” principle applied. Russian petroleum exploitation activity was mainly focused on other areas of its vast territory, but it also conducted some operations in the area of the Caspian adjacent to its coast and ultimately reached agreement with Azerbaijan on demarcation of the respective offshore areas.

A similar situation developed offshore Kazakhstan. Exploration activity in the northeast Caspian area adjoining the coast of Kazakhstan began in 1992 when the government announced a programme which attracted participation from some of the biggest players in the international industry. The gigantic Kashagan field was discovered in 2000 and quickly moved towards development by a consortium of those companies.

Azerbaijan and Russia agreed bilateral treaties, the most significant of which was signed in 2002. Similar processes took place between Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan and between Kazakhstan and Russia. Most significantly, in 2003 the three countries signed the Tri-point–Border Agreement on the junction point of lines delimiting adjacent zones of the seabed and subsoil.

Although Iran denounced these treaties as invalid, the result was that, so far as the three states bordering the northern part of the Caspian were concerned, the seaward boundaries between them were settled at least for the purposes of hydrocarbon exploitation and production. However, Russia continued to oppose the right to construct pipelines on a bilateral basis.

In the southern part, there were fields in the central area which were actively disputed. In 2001, an Iranian warship threatened to fire on a research vessel from Azerbaijan that was conducting operations there.

Turkmenistan generally remained much more inward-looking than its northern neighbours. Some of this may be explained by its relatively small population and huge onshore gas reserves, which have been mainly of interest to its neighbours – Russia, China, and Iran. The big international oil and gas companies which have been active in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Russia have occasionally showed interest in Turkmenistan but declined to invest. Nonetheless, Turkmenistan has also attracted some independent companies, including offshore, where the Cheleken field is currently in production.

Considerable international interest has been expressed in exporting gas from Turkmenistan through a pipeline that would cross the Caspian, but the development of a trans-Caspian pipeline in the southern part of the sea has begged difficult questions that until recently (with the signature of the 2018 treaty – see below) seemed unlikely to be resolved. It remains to be seen whether and to what extent this may now change.

Environmental sensitivities – ecology and biodiversity

There are exceptional environmental sensitivities about ecology and biodiversity in the Caspian. One peculiarity is that its northern part is very shallow and the southern part deep, and this creates unusual problems.

It is of course, the main home of the most prized species of sturgeon and therefore the source of much of the world’s top-grade black caviar. There are concerns about overfishing and the beluga is classified as critically endangered.

In addition, scientists have expressed serious concerns over the state of the seabed, which are inevitably raised in relation to proposed activity which might disturb the seabed. Russia has raised such issues repeatedly in relation to a potential gas pipeline to run along the seabed between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan.

The 2018 Convention

The Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea was signed on 12 August 2018 on behalf of all five littoral states, after many years of working group negotiations starting in 1996. It resolves some of the issues outlined above but not all of them. Nonetheless, it is a great achievement.

Special Legal Status

The Convention declares in Article 2 that the parties

“shall exercise their sovereignty, sovereign and exclusive rights, as well as jurisdiction in the Caspian Sea in accordance with the Convention”

and that the Convention defines and regulates the

“ rights and obligations of the Parties in respect of the use of the Caspian Sea, including its waters, seabed, subsoil, natural resources and the airspace over the Sea”.

In effect this resolves the sea-lake issue by establishing a special legal status, as set out in the Convention, that applies. Indeed, the Convention defines the Caspian Sea not as a sea or a lake but rather as “a body of water surrounded by the land territories of the Parties”.

Key features for petroleum exploitation

Much of the Convention focuses, as might be expected in a treaty reflecting a general settlement in relation to such a body of water, on fishing, navigation, naval and military use, scientific research, and ecology.

There are two features which are key so far as exploitation of petroleum resources of the seabed and subsoil are concerned.

Article 8 provides that

“Delimitation of the Caspian Sea seabed and subsoil into sectors shall be effected by agreement between States with adjacent and opposite coasts, with due regard to the generally recognized principles and norms of international law, to enable those States to exercise their sovereign rights to the subsoil exploitation and other legitimate economic activities related to the development of resources of the seabed and subsoil”.

In effect this legitimises the existing bilateral treaties between the states of the northern Caspian and generally follows the principles established by UNCLOS.

Article 8 also provides a right for a coastal state to develop artificial islands within its sector. The northern Caspian being so shallow, it was necessary to build an artificial island to enable operations on the Kashagan field to take place effectively, and Article 8 legitimises that (as well as other such islands that might be similarly necessitated).

Article 14 provides as follows.

“1. The Parties may lay submarine cables and pipelines on the bed of the Caspian Sea.

2. The Parties may lay trunk submarine pipelines on the bed of the Caspian Sea, on the condition that their projects comply with environmental standards and requirements embodied in the international agreements to which they are parties, including the Framework Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Caspian Sea and its relevant protocols.

3. Submarine cables and pipelines routes shall be determined by agreement with the Party the seabed sector of which is to be crossed by the cable or pipeline.”

This, in principle, opens the way to a Trans-Caspian Pipeline that could be agreed between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan. However, the conditions of Article 14 are such that other littoral states would inevitably have rights to express concerns which could delay or, ultimately, impede (or maybe even indefinitely block) such a development.

Disputes

The Convention does not provide a mechanism for dispute resolution between the states. It also does not provide for investor-state dispute settlement.

What it says about disputes is as follows (in Article 21).

“1. Disagreements and disputes regarding the interpretation and application of this Convention shall be settled by the Parties through consultations and negotiations.

2. Any dispute between the Parties regarding the interpretation or application of this Convention which cannot be settled in accordance with paragraph 1 of this Article may be referred, at the discretion of the Parties, for settlement through other peaceful means provided for by international law.”

The main benefit of this is that it does at least refer the parties to mechanisms of public international law – which are by now relatively well established – to resolve disputes between them. Whether this is used to resolve the boundary issues in the southern Caspian – and, if so, how - remains to be seen.

The concluding words of the Convention provide that, although there are original copies in the Azerbaijani, Farsi, Kazakh, Russian, Turkmen and English languages, all texts being equally authentic, in case of any disagreement the parties shall refer to the English text.

Ratification

Four of the five parties to the Convention have ratified it, the last being Russia which passed a ratification law that was signed by President Putin on 1 October 2019.

However, the Convention itself provides that it shall come into force on the date of receipt by the Depositary (the Republic of Kazakhstan being so designated) of the fifth instrument of ratification. Although the Convention was approved by the Islamic Republic Supreme National Security Council before it was signed, it remains to be formally ratified by Iran. In view of the substantial domestic opposition to the Convention following its signature, it might be a long time before this eventually will occur.

Doran Doeh

International Arbitrator

36 Stone, London